Temperate Forest Restoration: A Study of Restoration Initiatives and Methods Worldwide

A study of temperate forest restoration techniques worldwide, and what it means for conservation evolution

RESEARCH PIECES

Charlie Manta & Kaden Theisen

1/10/202534 min read

Abstract

This paper will explore Project Drawdown’s climate solution, Temperate Forest Restoration, and its effectiveness in our modern world as we face increasing environmental destruction and climate change. We will present our perspectives as informed by our research within the Appalachian Mountain Region, studying initiatives that have taken place and the effectiveness of Project Drawdown’s “natural restoration” methods. We will present three case studies involving temperate forest restoration efforts from around the world, including Europe, Chile, and New Zealand, and apply our findings from these efforts and different worldviews to the restoration efforts in the Appalachian Mountains. This exploration of varying forest restoration efforts will result in a guide beyond an Americanized worldview. By researching temperate forest restoration efforts from these different regions, we plan to develop an all-encompassing study of assorted initiatives for temperate forest restoration to contribute to more accessible, effective, and efficient solutions.

Introduction

Temperate forests constitute about 25% of our planet’s forests - approximately 766 million hectares of land. This biome is an imperative part of our ecosystem due to the many ecosystem services and carbon-sequestration abilities it provides. The world’s temperate forests can sequester 19.42-27.85 gigatons of carbon dioxide by 2050 (Maldvakar et al.). These forests are home to an extensively biodiverse range of flora and fauna species, sequester carbon in trees and soil, reduce erosion through vast tree root systems, and can help provide water for agricultural use, city use, and hydro-power (Galicia 2014, 275).

Temperate forests provide a home for an expansive list of plants and animals and offer services that hold social and economic significance beyond the environment. Provisioning services such as food and timber contribute to economic benefits for companies that make a profit from logging and other activities that require deforestation but also contribute to their inevitable downfall as our profit-driven society searches for ways to exploit temperate forests for their natural resources (Galicia 2014, 276). This exploitation leads to declines in other ecosystem services, including nutrient cycling, the regulation of flooding, and recreational activity. Many of these services can be observed in our Appalachian region.

Immediately upon stepping foot into the Blue Ridge Mountains, one can observe various plants and animals making their home in these forests. This complex yet essential web of ecosystem services requires us to develop an all-encompassing method for management and restoration.

As our world develops and changes to accommodate a rapidly growing population, effective temperate forest restoration methods are essential to sustain and preserve these biodiverse and beneficial ecosystems. The planet’s forests have faced decades of change at the hands of human activity. Currently, 13 million hectares of forestland are deforested globally each year (Dumroese 2014, 948). Temperate forests tend to be concentrated near urban areas or areas with a high population density, which results in increased burdens and stressors from human activity. This can be seen in different forms, including pollution, mismanagement, land use changes for various activities, including agriculture or mining, and the introduction of pests and diseases (Adams et al. 2019, 85). As we develop as a society, so does our need for natural resources. Unsustainable practices have led us to become a burden on these forests.

Climate change is a rapidly evolving threat to these forests, the consequences of which are already being observed. The effects of climate change, including higher temperatures and variations in precipitation patterns and natural weather events, are evolving threats that may impact our current temperate forests and how they can be restored. Many tree species within these forests may be unable to adapt to and overcome these changes (Dumroese 2015, 949). The consistent degradation and exploitation of the land contributes to its inability to recover from our actions, as “the addition of new disturbances leads to loss of biodiversity that reduces ecosystem response to perturbations, destabilizes the system, and ultimately leads to a loss of function” (Dumroese 2014, 948). The need for effective restoration in the face of anthropogenic climate change and environmental degradation is great.

Based on this urgent need for restoration, this study considers different restoration techniques worldwide. Temperate forests occur in mid-latitude regions, specifically between the tropical and polar regions, including North America, northeastern Asia, the majority of Europe, and Oceania. With such a widespread occurrence comes a wide range of restoration techniques and uses of the land (Adams et al. 2019, 83). In this study, we will focus on three of these regions - Europe, Chile, and New Zealand- and examine how their various approaches to temperate forest restoration can be seen or utilized within the temperate forest most familiar to us: the Appalachian Mountains.

Given the multitude of reforestation techniques and values, our goal is to employ several global perspectives on land and restoration, expanding upon the individualistic efforts that different regions may be implementing. By examining temperate forest restoration initiatives and mindsets from around the world, we hope to inspire and create new restorative efforts to implement a solution promptly and effectively, combatting the ever-evolving threat of global climate change. The goal of this piece is to provide a multi-level framework that considers environmental, social, and economic needs in the process of temperate forest restoration.

Modern Management and Restoration

Different management and restoration systems can be seen globally, including natural and planted stands, ranging from “highly managed plantations to vast wilderness” (Adams et al. 2019, 85). The status of different forests globally is variable, as some forests are expanding through “re-wilding” initiatives following deforestation and agricultural land development, while some forests are still seeing depletion due to these exploitations of the land. Some of these initiatives take a hands-off approach to let nature run its course and encourage natural growth, while other forests rely on forest plantations and human intervention.

“Functional restoration” is a mindset that involves and strives to “bring back or improve a condition in which the regular function(s) that contribute to a forested system are present” (Dumroese 2015, 950). A central feature of this restoration strategy is focusing on what the forest provides to the environment and how its ecosystem services thrive rather than focusing on species composition and what trees make up these forests. This could involve placing ourselves into the restoration process of human-altered forests through silviculture techniques such as tree thinning, re-introducing “natural fire regimes,” or interplanting. This method includes one or more of four strategies: rehabilitation, reconstruction, reclamation, or replacement (Dumroese 2015, 950). This means that functional restoration depends on human intervention to restore the forests that were once lost. However, this kind of direct approach is not seen or supported worldwide.

Other initiatives, such as Project Drawdown, support a natural restoration approach, where it is up to nature to take control of regrowth without or with limited human intervention. This study takes a further look into various restoration and management practices globally, from past to present, as an introduction to a comparison between different approaches. This piece aims to draw attention to the concept that no single method can be applied to every region with the same outcome and level of effectiveness. However, there are critiques and changes that could be made to our current approaches when looking at temperate forest restoration through a wider lens, as we will look into, especially in the Appalachian region.

Project Drawdown’s Temperate Forest Restoration Solution

Project Drawdown presents a multitude of climate solutions that are necessary for undertaking action against climate change. Temperate Forest Restoration is an integral piece of the climate-solution puzzle, as “almost all temperate forests have been altered in some way—timbered, converted to agriculture, or disrupted by development” (Maldvakar et al.). Anthropogenic activities such as deforestation and surface mining have contributed to destroying these important forests, giving us the responsibility of restoring them to their original nature. Temperate forests are a carbon sink, “typically containing 100 metric tons of carbon per hectare” (Lal and Lorenz 2012, as quoted by Maldvakar et al.). The destruction of these forests prevents this from occurring. According to Project Drawdown, While ninety-nine percent of temperate forests have been altered, more than 1.4 billion hectares could be restored.

Project Drawdown’s approach towards temperate forest restoration involves natural regeneration, which involves taking a step back and “allowing natural regrowth to occur'' (Maldvakar et al.), which can be seen as contrary to other methods such as functional restoration, as previously mentioned. There can be challenges to this approach, as logging and mining companies rely on altering the land for economic gain and job security in our ever-evolving profit-driven economy, and creating an initiative to combat these issues can have major hurdles. According to Project Drawdown, “natural regeneration is low cost and also offers co-benefits such as biodiversity conservation, watershed protection, soil protection, and resilience to pests and disease.” Through this method, Project Drawdown declares and expects 92.64–128.38 million hectares to be restored by 2050 (Maldvakar et al.). Considering the median of this range, about 110.5, Project Drawdown aims to restore about 15% of these 766 million hectares of forestland within the next 30 years.

While these numbers sound incredibly beneficial and guide us toward a hopeful future for our planet and specifically for temperate forests, it leaves the question of how well this hands-off approach can be applied to different regions of the world and if other methods could be applied to and learned from various temperate forests around the world. If the year 2050 is our current goal in achieving this level of restoration, how much can be left up to nature, and how much should we as a society intervene?

The History of Appalachia’s Temperate Forests

The temperate forests of the Appalachian Mountains are home to mature and sizeable trees, lush forests, productive soil, expansive biodiversity, and more. Humans have impacted this land for centuries, both beneficial and harmful. Colonization by European settlers led to an overbearing burden on the land by excessive and exponential development and agriculture. Livestock and agriculture have impacted the land, but “widespread and unregulated corporate logging” made the most detrimental impact (Barton and Keeton 2018, 64). This continued from the 1800s to around 1930, with intensive logging followed by unregulated slash-and-burn operations and immense soil erosion. Areas with such intensive logging from this era, leading to severe soil erosion, still lack complete tree cover.

Now, one of the largest threats to Appalachia’s temperate forests is coal mining, which contributes heavily to land degradation and fragmentation. Over 600,000 hectares of Appalachia’s land have succumbed to coal mining (Zipper et al. 2011, 752). The forests that are not completely destroyed due to surface mining become fragmented, which causes the biodiverse interior of a thick forest to be lost to edge forests at a rate that is “five times greater than regular forest loss” (Perks 2010). Fragmentation of this rate leads to an immense loss in ecological function, and we see a decline in the important ecosystem services that this biome provides. The Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 was formed to combat these effects of coal mining, intending to “stabilize land surfaces, including surface compaction by mining equipment and rapid establishment of dense herbaceous vegetation” (Zipper et al. 2011, 752). This effort turned out to be burdensome, unintentionally resulting in land surfaces that hindered the ability of native trees and plants to regrow and perform. This was due to the overplanting of ground covers and fertilizer application, resulting in competition for nutrients and sunlight, and the compacted soil prevented tree roots from growing.

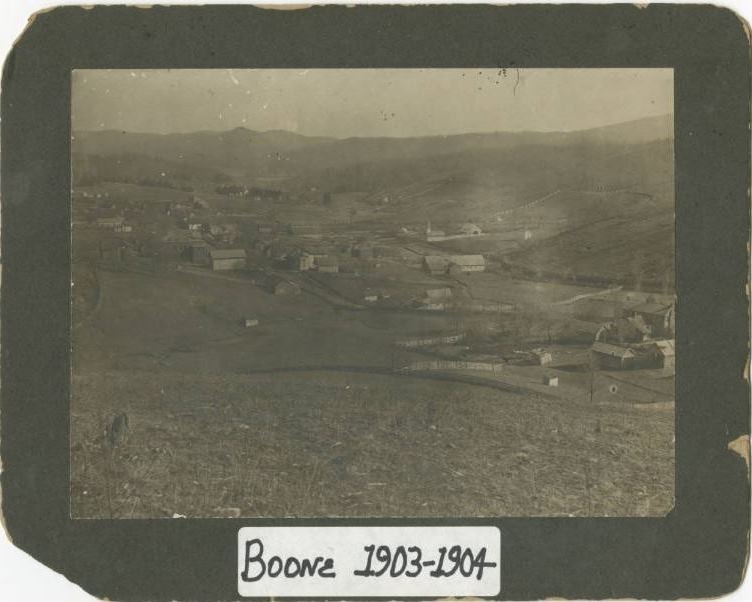

Fig. 1 This image shows Boone, North Carolina, circa 1903-1904. This image shows a noticeable lack of trees in the midst of logging, which is a major industry in Southern Appalachia (image from Digital NC).

Temperate Forest Restoration Initiatives of the Appalachian Region

Restoration initiatives have occurred resulting from these destructive mining and reclamation practices. The Forestry Reclamation Approach was developed in response to these mining practices in the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act, with five specific steps that can be applied by coal mine operators (Zipper et al. 2011, 752). The first step, as declared within the Forestry Reclamation Approach, is creating a “suitable rooting medium for good tree growth that is no less than four feet deep and comprised of topsoil, weathered sandstone, or the best available material” (Zipper et al. 2011, 753). The following step directs us to grade the topsoil or topsoil substitutes, which had been established in step one, to create a medium for non-compacted soil growth (Zipper et al. 2011, 754). Then, reduce the use of competitive ground covers that hinder tree growth. Subsequently, we must plant “early successional species for wildlife and soil stability, and commercially valuable crop trees” (Zipper et al. 2011, 755). Finally, to ensure the effectiveness of these steps, it is important to implement proper tree-planting techniques. These steps work to commence restoration while avoiding over-compensating for the damage done. This is essentially a step above natural regeneration by influencing regeneration but not completely taking over with human intervention.

Many temperate forest restoration initiatives and organizations exist within this region. The Appalachian Regional Reforestation Initiative is a “coalition of groups, including citizens, the coal industry, and government dedicated to restoring forests on coal mined lands in the Eastern United States,” with various state agencies (“Appalachian Regional Reforestation Initiative”). This initiative involves a collaborative effort between the States of the Appalachian Region and the Office of Surface Mining to restore devastated temperate forests (Angel et al. 2005, 1). The goals of this initiative are to plant high-value trees within the region and on reclaimed coal mines, increase tree survival rates and growth, and speed the process of forest habitat establishment, specifically through the use of natural succession. Natural succession ties into the Forestry Reclamation Approach, as previously mentioned. Using this approach, “highly productive forests can be created on reclaimed mine lands under existing laws and regulations” (Appalachian Regional Reforestation Initiative). The organization also hosts tree-planting events on surface-mined lands and is home to many tree seedling nurseries.

The Nature Conservancy’s Conserving the Appalachians program shares necessary information on the importance of these mountains, their temperate forests, and key strategies for conserving and regenerating. Similar to previously mentioned methods, the Nature Conservancy’s approaches are founded in nature. This organization has multiple goals, which include creating a connected landscape of climate-resilient lands and waters through corridors and blended biomes. They also aim to “leverage land and water conservation to provide critical natural climate solutions for healthy communities and resilient landscapes” and “aid the capacity of local conservation organizations, Indigenous Peoples and local communities to help conserve high priority lands and waters” (Conserving the Appalachians). This places emphasis not only on protecting our physical environment but also on taking into account the human lives that are affected and ensuring an equitable outcome for all who are impacted by this issue and live in this region. Mapping is used by this organization to portray the importance of these biomes and their contribution to biodiversity. Many efforts are being made in the Appalachian region by multiple organizations and initiatives to restore our beloved temperate forests.

Fig. 2 This map by The Nature Conservancy depicts “Nature’s Highways,” portraying the significance of the Appalachian Temperate Forest Biome for biodiversity and the movement of animals (Created by Dan Majka).

Traditional Ecological Knowledge

We cannot properly address temperate forest restoration without considering the methods of indigenous people who have lived on the land for millennia. One of the current ways this is taking place is through Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK), which is “an understanding of ecosystems acquired through long-term observations by people inhabiting a region… TEK is often encoded in rituals, beliefs, and cultural practices” (Souther et al. 2023, 1). This section aims to give an overview of TEK and how it relates to temperate forest restoration.

Traditional Ecological Knowledge can create critical cultural shifts. In the past, it has made people who have used natural resources in an unsustainable way feel the consequences of their actions (Souther et al., 2023, 3). In the modern day, unsustainable use of natural resources is frequently felt in the worst ways by those who reside in the Global South or poorer communities rather than those committing unsustainable actions. Having a greater understanding of what people are doing by acting in these ways could help create cultural shifts that prevent them from acting that way in the future. TEK can help improve education about how ecosystems work (Souther et al., 2023, 4). Indigenous legacy has involved altering the environment in ways that are mutually beneficial and neglecting to recognize that will only hurt our learning opportunities (Souther et al., 2023, 4).

Traditional Ecological Knowledge can also be beneficial as it involves long-term knowledge that can explain unexpected or novel ecosystem changes (Souther et al. 2023, 5). For example, some tribes followed and recorded migratory patterns of the fish they could eat and may be able to better identify irregularities than modern Western methods (Souther et al. 2023, 5). TEK can also be another form of setting goals for restoration strategies and may be able to provide quicker warnings about endangered species and environmental transitions (Souther et al., 2023, 5). This has been observed in the case of Arizona’s Apache Tribes, who managed to attribute a decline in acorns to specific and preventable factors. This warning allowed land managers to identify this acorn species as a conservation concern before it faced irreversible declines (Souther et al. 2023, 5).

Traditional Ecological Knowledge also frequently takes an all-inclusive approach that has been absent in many past restoration efforts, causing them to fail due to a lack of collaboration on smaller scales (Souther et al., 2023, 5). Failing to recognize traditions has also been an issue that creates unrest among smaller communities that were ignored or disrespected (Souther et al., 2023, 6). TEK is, therefore, helpful in gaining wider support, stewardship, and involvement as “local values and priorities are incorporated into land management practices, creating a shared vision for governance” (Souther et al., 2023, 6). To properly take action toward temperate forest restoration and achieve a more inclusive future, we must incorporate Traditional Ecological Knowledge into our practices.

Case Study #1: “Challenges of ecological restoration: Lessons from forests in northern Europe” (Halme et al. 2013)

To determine the best ways to move forward with forest restoration, we studied scholarly articles that analyzed restoration efforts from different temperate forests worldwide. The first region this paper analyzes outside of the United States is Europe. It may not be the first continent that comes to mind when people think about places for biodiversity or dense forests, as it is the second smallest continent with the second-highest population density (WorldAtlas 2019). The region is very well-known for its human history, especially the millennia of wars that have taken place on European soil, causing catastrophic losses to human lives and nature. However, the implications of temperate forest restoration in Northern Europe, specifically, are significant as the exploitation of forests is high, and their biodiversity values are decreasing (Halme et al. 2013, 248). In this section, we will look at the challenges of restoration initiatives that have occurred and suggest our strategies for forest restoration on various scales.

In the past few decades, efforts to protect and restore biodiversity have been a significant part of the global political agenda, and the European Union has adopted ideas that support this as part of the 2020 Biodiversity strategy (Halme et al. 2013, 249). The term ecological restoration may be interpreted and understood in different ways. According to Halme et al., it implies two ideas: the goal of bringing an ecosystem back to a former condition, and the second is maintaining stewardship of the land to bring it to its desired condition. They also stressed the idea that restoration does not necessarily signify bringing the land to some perfect, untouched state but instead as a key goal in the process of conservation (Halme et al. 2013, 249). Restoration is an action focused on the past, present, and future. The ecosystems need to be resilient against whatever the future holds, which can be achieved through an environment that has a variety of plant and animal species that are protected and healthy (Halme et al. 2013, 249).

Challenges of ecological restoration: Lessons from Forests in Northern Europe analyzes the history of forest restoration in North Europe, which, according to Halme et al., can be characterized by a strong focus on increasing biodiversity. Studying restoration efforts in northern Europe is beneficial to enhancing understanding of it for three main reasons: the forests are in a variety of different conditions, from heavily exploited to essentially untouched; the understanding of European forests is already high because of a long legacy of research; and restoration actions and research/ monitoring have been increasing at a significant rate allowing researchers to understand what is best for the ecosystems (Halme et al. 2013, 250).

Through analyzing the functionality and human stresses, including the losses, restoration efforts, and the possibility of being able to or not restoring certain ecosystems, this paper concluded that there were five main lessons to be learned (Halme et al. 2013). This section will work to apply the lessons to restoration efforts in Appalachia and discuss how the challenges can be addressed. The first lesson describes how it must be explicitly understood what that ecosystem needs rather than taking a broad view (Halme et al. 2013, 253). We can still use knowledge from other places to inform our decisions, but no algorithm single-handedly restores a forest. To ensure all places where restoration efforts are taking place are properly looked after and not just following a general plan, we suggest utilizing a bottom-up approach. This is in response to the past failings of top-down policymaking that typically entail higher costs and are not specific enough to the places they are supposed to be helping (Apfelbaum et al. 2013). Bottom-up approaches ensure that the people who live in or near where restoration is happening are involved, and it allows for educational opportunities that create lasting benefits (Apfelbaum et al. 2013). This is especially beneficial in Appalachia, where many people take great pride in where they live and have family history dating back centuries.

The second lesson to be learned was to “be aware of the problems in defining naturalness” (Halme et al. 2013, 253). This section discusses how ecosystems today are constantly changing and may require different restoration techniques than they once did to ensure their resilience (Halme et al. 2013, 253). Halme et al. suggest that to achieve this, we need to use another ecosystem as a reference point. We agree with this point and suggest that we can locate a reference ecosystem by analyzing four main components: successful restoration efforts in the last twenty years; issues faced in the past, present, and future; biodiversity; and climatic conditions (temperature, precipitation, humidity). Locating an ecosystem that contains these similar components will allow us to use the knowledge as a baseline for efforts in the targeted area of restoration. Many environmental organizations have locations in different states, which allows for communication between one another to understand how they address issues. For example, The Nature Conservancy, an organization “tackling the dual threats of accelerated climate change and unprecedented biodiversity loss” (The Nature Conservancy 2024), works in every state in the US, allowing easy communication from state to state that would help locate reference ecosystems. This approach also addresses lesson four, which is to “set proper targets and monitor progress” (Halme et al. 2013, 253). Having reference sites can be used as a form of long-term, dynamic monitoring as the reference site will change and set an evolving precedent for what restoration efforts should involve (Halme et al. 2013, 253).

The third lesson is to “assess whether restoration is needed and can be successful with feasible resources” (Halme et al. 2013, 253). Some factors that need to be accounted for when deciding whether restoration is possible and necessary are the forest’s current condition, the condition of the local landscape, and whether the ecosystem can be restored naturally with no additional steps taken (Halme et al. 2013, 254). A way to do this is to utilize the Reforestation Hub, which “maps out relatively low-cost and feasible options to restore forests across the contiguous U.S” (The Nature Conservancy & American Forests, 2023). This database addresses whether it is needed because it finds specific areas where restoration is needed and whether it is feasible. The Reforestation Hub addresses cost-effectiveness and specific steps to achieve restoration. According to the Reforestation Hub, reforestation in the contiguous United States “with approximately 76.2 billion trees could capture 535 million tonnes of CO2 per year, equivalent to removing 116 million cars from the road.” In Watauga County alone, there is the potential to sequester 165,000 tonnes of CO2 (The Nature Conservancy & American Forests 2023). The Reforestation Hub also supports Project Drawdown’s focus on carbon sequestration.

The final lesson is, “If you still have it – do not destroy it” (Halme et al. 2013, 254). While this appears obvious, it stresses the importance of conservation efforts and the role of passive restoration. By measuring biodiversity values and leaving the areas with high values alone, we can save money and time and focus on places that need more work (Halme et al., 2013). We can protect areas through legislation by writing letters to politicians and voting people into office who prioritize conservation. Activism, a focus of many environmental organizations, can help pressure legislators to do more for the protection of forests, and it can inspire people to take action in whatever way they can. A local organization that is a prime example of these actions is the Blue Ridge Conservancy, which “partners with landowners and local communities to permanently protect natural resources with agricultural, cultural, recreational, ecological and scenic value in northwest North Carolina” (Blue Ridge Conservancy, ‘Our Mission’). Organizations like this are crucial for achieving preservation/conservation goals and engaging communities on smaller scales.

Case Study #2: “Streamflow response to native forest restoration in former Eucalyptus plantations in South-Central Chile” (Lara et al. 2021)

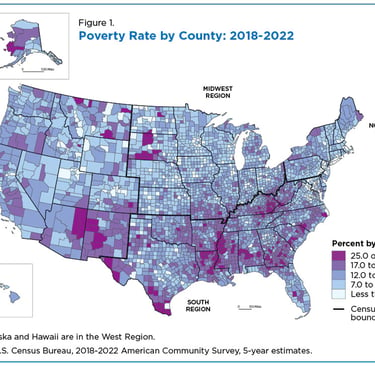

Chile is a unique area in which to analyze forest restoration efforts as it is the only place we are analyzing that is a developing country. South America, as a whole, “has among the highest global rates of native forest loss and plantation forest establishment” (Lara et al. 2021, 2). This study in the Valdivian Coastal Reserve can help us relate efforts to Appalachia, where there is a significant history of deforestation (fig. 1) and high poverty rates (fig. 3).

Fig. 3 This map made by the United Census Bureau shows poverty rates by county in the United States from 2018-2022. The poverty rate is shown on a scale with white representing the lowest poverty rates and purple representing the highest poverty rates.

As shown in Figure 3, Southern Appalachia has some of the highest poverty rates in the United States and shows significant underdevelopment similar to that of the Global South (US Census Bureau, 2023).

While there are many observed benefits to the restoration of forests, it is also necessary to consider the impacts that result from these efforts. More specifically, Lara et al. observed the fact that there were very few studies on the hydrologic impacts of native forest restoration. Their novel study is a “14-year (2006 to 2019) catchment study, which covers the response of streamflow to the first 9 years of a native forest restoration process that will require at least 130 to 180 years to attain mature or old-growth forest structure,” as well as comparing the effects of forest restoration and the current Eucalyptus plantation (Lara et al. 2021, 2).

The results of this experiment have major implications for informing future decisions regarding temperate forest restoration. It provided the “first evidence from a paired catchment experiment that the early stages of native forest restoration can increase base flow and dry season (summer, fall) flow” (Lara et al. 2021, 11). As the effects of climate change continue to dry up rivers and reduce streamflow, it is critical that we evaluate the ways in which we manage our forests and go about restoration. It is also imperative that communities, cities, states, and countries everywhere analyze how they manage the current land. Following the removal of Eucalyptus Plantations in certain locations in the Valdivian Coastal Reserve and nearly a decade of native forest restoration, there was a “gradual recovery of annual base flow… and pronounced increase in base flow during the last 3 years of the study, despite low precipitation in the last 2 years” (Lara et al. 2021, 14). Therefore, one way that we theorize we can address climate change issues, such as drought, is by reforesting areas where monoculture was once present, which can be observed in abandoned farmland. A study done by Wright et al. in 2021 observed eight different species of forbs and grasses growing in a monocultural environment compared to places with greater biodiversity. According to their study, “Six of our eight species performed poorly when growing in monoculture during dry years but not wet years… These same species were unaffected by drought when growing in higher-diversity mixtures” (Wright et al. 2021, 1). Because of this, we believe that taking action to restore these areas where agriculture once took over forests will create an ecosystem with rivers and species of plants and animals that are significantly more drought and flood-resistant.

To accomplish restoration in this sense, it is important to understand the potential that the land has to be restored. As mentioned in the previous section, one of the ways to do this is by utilizing the digital Reforestation Hub. The Restoration Hub is a solid baseline for understanding where forest restoration efforts may go the furthest and whether passive or active restoration methods may be necessary, as discussed in the previous study. However, it is not the only way: once an area is identified as a potential project for restoration, there will be three important next steps. The first will be studying what species of plants and animals have created productive, healthy conditions on this land in the past. This can be done by analyzing various written historical records and photographs. This analysis will help understand past uses and causes for the condition it is in today.

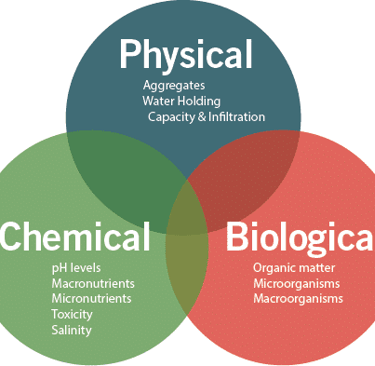

The next step will involve actively going to the sites and evaluating their condition. Using the standards of the United States Fish and Wildlife Service of what makes a forest healthy, including rich biodiversity, various habitats, good water quality, trees of different ages, and trees that are not too close together (Robinson 2022), we suggest the following steps for evaluating the condition of the forests. This would involve taking soil samples, observing biodiversity levels, testing water quality, recording tree density, and observing the quality and presence of habitats. It is important to understand what to look for when testing soil. Figure 4 communicates these specific measurements that can be taken.

Fig 4. This image produced by PhycoTerra lists the indicators to test for to measure and understand soil quality.

Biodiversity can be measured by dividing the number of species in the area by the number of individuals in the area (Oxford Reference, n.d.). Overly dense trees can be harmful, which means some trees do not receive adequate sunlight (Robinson, 2022). Therefore, it is critical to observe tree density. One critique of this idea may be that it requires excessive work on such small scales to try to record this much data. However, this is an opportunity to organize students of higher levels of education to take place in the process, providing hands-on experience. Building from this concept, we suggest that courses allow students to participate in sustainable restoration efforts as a contribution towards course credit. For example, biology or agroecology courses would likely have the necessary understanding to record this data. This can also be done by local organizations, whether it involves paid or volunteer work. Most of the indicators are fairly easy to measure and could be done properly with adequate education and oversight.

The final step will involve conducting studies similar to the one done in the Valdivian Coastal Reserve, where we compare and contrast the effects of the restoration practices. This will be a project that evolves over time, and yearly evaluations will be part of the ongoing process. By using reference ecosystems as mentioned before, we can see if these practices are working or if changes in restoration practices need to be made.

Case Study #3: “Opportunities and limitations of exotic Pinus radiata as a facilitative nurse for New Zealand indigenous forest restoration” (Forbes et al. 2019)

In this case study, we will dive into a more alternative approach to temperate forest restoration and introduce concepts that are typically not seen in the Appalachian region. New Zealand is home to expansive and vital temperate rainforests. Anthropogenic activity, specifically human habitation, has caused great reductions in the temperate rainforest coverage of this region. An estimated 71% of New Zealand’s temperate rainforests have been cleared over time, immensely impacting the country’s biodiversity and ecosystem services (Forbes et al. 2019, 2).

New Zealand has faced a long and complex history with logging practices. Between 1850 and 1960, the logging industry gained most of its resources from indigenous tree species and lacked proper regulations that limited this practice (McGlone 2022, 1). In an attempt to interfere with unregulated logging in 1945, the State Forest Service was enacted to manage the land (McGlone 2022, 8). Indigenous logging was especially utilized during World War II as a cheap and easy approach to resource extraction, but the State Forest Service made attempts to direct logging away from indigenous species (McGlone 2022, 9). To appease both conservationists and logging companies, the Service created a plan where forests with nutrient-deficient soils and suboptimal climates would be maintained and protected for “sustainable” logging or protection forestry, and areas of forest with better soil and climate conditions would be reserved for clear-cutting and conversion to agricultural land (McGlone 2022, 8).

The New Zealand government tended to side with pro-development and timber companies, which made it difficult for the Service to enact their proposed limitations. Finally, around the 1960s-1970s, emphasis was beginning to be placed on preservation and retaining old-growth forests. Exotic timber was now the focus for logging, and the State Forest Service implemented very specific policies. This includes only using clear-felling techniques when a “clear need” is apparent (McGlone 2022, 10). Social, environmental, and economic factors all need to be analyzed and considered, and logging should only occur when all three of these sectors would benefit. An analysis must be conducted to determine whether the production of timber is more important than other conflicting values, such as preservation. Finally, logging should leave “open the options of maintaining an indigenous forest structure with a wide range of values or clearing for other uses at some unspecified future time” (Conway 1977, as quoted by McGlone 2022, 10).

Attempts are made to combat deforestation and make reparations to the land from this intensive history of logging through the implementation of commercial plantations, which “might contribute ecologically by increasing landscape connectivity, buffering indigenous remnants, or providing sometimes scarce forest habitats” (Forbes et al. 2019, 2). However, the long-term potential of these plantations is reduced as these operations can be invasive and disturbing. There is a gap in this restoration effort where trees are being planted, and restoration efforts are implemented and succeeding to a certain extent. However, there is still a loss in indigenous species and natural regeneration. About 90% of these commercial plantations consist of the Pinus radiata tree species, which is native to North America. While this is the case, there are instances of foreign tree implementation seen in New Zealand that have helped promote forest regrowth and conservation.

Few studies have shown that introducing and planting this foreign species is, in fact, beneficial to the temperate forest restoration of this region. Due to different environmental, social, and economic reasons, it is unlikely for this species to be harvested at the rate that indigenous and native species would be (Forbes et al. 2019, 2). This can actually present opportunities for indigenous species regrowth. Forbes et al. introduce a European study by Onaindia et al. 2013, which presented the idea of Pinus radiata plantations as a “passive restoration tool,” where this foreign species would essentially be mixed in with indigenous forest species as a tool to encourage growth and restoration. The concept behind this line of thinking is that these tree species can help encourage forest growth and fill in gaps in clear-cut areas. If deforesting does occur, these foreign species should be utilized first rather than striking native species. This implements a similar Forestry Reclamation Approach as previously mentioned, with more guidance and species introduction. It was found that as these mixed forests aged, they grew into similar forests to the fully indigenous and biodiverse forests that once stood in these European regions.

This journal continues with an investigation of the “long-term potential of non-harvest P. radiata plantations in recruiting indigenous forest flora and developing a forest community dominated by indigenous woody species, characteristic of mature natural forest” (Forbes et al. 2019, 2). It is hypothesized that the outcomes are dependent on suitable light levels within the forest, as well as the ability of different species to disperse and reach the site from indigenous forests. The study takes place in Kinleith Forest, an example of one of New Zealand’s commercial exotic plantations. Nine Pinus radiata plantation stands had been examined in different proximities to the indigenous temperate forest. The growth of these trees influenced the local species and how they grew while adapting to this new canopy coverage. Native tree species with large seeds, an ability to grow to a considerable size, and contribute to the tree canopy were found to grow and stand out the most due to the implementation of the Pinus radiata (Forbes et al. 2019, 7).

Proximity of these stands to indigenous forests was found to play a significant role. With closer proximity between the foreign tree stands and indigenous forests came “a greater density of indigenous woody seedlings and a greater abundance of mature forest canopy species of closer compositional similarity to indigenous forest.” (Forbes et al. 2019, 7). Implementing these foreign tree stands seemed to aid in the growth of the indigenous forest canopy and create a plentiful, balanced ecosystem. While the composition of this forest is no longer purely indigenous, it can still carry out the ecosystem services seen before forest destruction.

The process by which temperate forest ecosystems grow and expand in New Zealand heavily depends on bird seed dispersal. The country has approximately 240 tree species, and about 70 percent of them have been dispersed by birds (Forbes et al. 2019, 9). While this is the case, seed dispersal by this method usually only occurs over shorter distances and with smaller seed sizes. When considering temperate forest restoration methods, it is imperative to consider the effectiveness of local seed dispersal by nature and how the implementation of foreign tree species can impact or assist with this. The available indigenous tree species in an area can play a major role in the determination of how a forest regenerates. If indigenous tree species are too far scattered, local bird species may not be able to effectively disperse their seeds. On the other hand, proper tree planting practices can lead to seed dispersal by birds, placing restoration efforts in the hands of nature and allowing us to take a step back.

Restoring sites from even-aged monoculture plantations presents a different restoration method, as the limited biodiversity can slow or prevent effective regrowth. Foreign tree stands dispersed in degraded indigenous forests can utilize more hands-off methods after the trees are planted, where it is up to the forces of nature to disperse seeds and grow. Restoration from a completely altered landscape may benefit from more intensive contact and labor. An example of this can be the formation of artificial canopy gaps or other interventions that essentially mimic natural events and growth patterns (Forbes et al. 2019, 10). The implementation of these interventions, which can look like stem poisoning or felling, early on can result in increased biodiversity further down the line of growth.

These methods highlight the importance of and methods toward indigenous temperate forest regrowth. Whether that is achieved through labor-intensive and hands-on methods early on in the process of re-growth, or planting tree stands to assist in the course of nature to regrow indigenous forests, is entirely dependent on the previous landscape and how the land has been used or forested. These methods and this line of thinking can be considered when initiating temperate forest restoration around the world, and careful studying of the land and growth patterns is necessary for a successful outcome.

The Appalachian region focuses heavily on either the Forestry Reclamation Approach or natural restoration as a cost-effective method to regrowing our beloved forests, but the clock is ticking on our ability to restore this biome promptly. Looking at the methods introduced in this article leads us to question the possibility of introducing more human intervention in our own forests and variation in our restoration techniques, whether it be by planting P. radiata tree stands around deforested land and on recovering surface mines or silviculture techniques such as thinning and forming artificial canopy gaps. While restoration is essential, it is also equally important that focus is placed on policy implementation and forest management to prevent intensive deforestation and environmental degradation from occurring in the first place.

Discussion

In a world where landscapes, history, methods, values, ecosystems, and economies are all vastly different and ever-evolving, it is imperative that functional temperate forest restoration methods are analyzed and implemented in the most effective manner possible. Each of these case studies presents concepts that could be analyzed and considered in the realm of Appalachian temperate forest restoration, which may be beneficial in conjunction with Project Drawdown’s approach.

A key point consistent among these case studies is the concept that forest restoration does not necessarily need to entail completely restoring a forest back to its original state but should emphasize conservation and preservation to the maximum extent possible. As focused upon by the European Union, temperate forest restoration needs to not only revitalize forests from past endeavors and exploitation but also prepare these biomes for future conditions, as needed for our ever-evolving world in the face of climate change. With one of the highest rates of deforestation in the world, to effectively restore temperate forest ecosystems in Chile at the rate necessary to combat climate change, a complete return to its untouched and indigenous state may not be what is necessary. Rather, restoration should be a goal in the process of conservation. We see this mindset utilized in New Zealand’s restoration efforts, where the implementation of non-native tree stands and silviculture techniques does not result in what would be an untouched indigenous temperate forest but rather a forest that is growing and becoming an ecosystem entity that will be able to withstand a developing world. This mindset is what Project Drawdown may be lacking. In the case of Appalachia’s recovery from surface mining, it may be beneficial to shift our focus from simply regrowing our forests and returning them to what once was into something that can withstand further exploitation and inevitable impacts from climate change and rapid development.

While an all-encompassing and effective restoration technique that meets all environmental, social, and economic needs through the use of highly specific tactics and intervention is desirable, our current economy does not necessarily allow that to occur. These case studies have presented concepts that, while they can be a bit more labor-intensive than a fully natural restoration project would be, could still be implemented in a cost-effective and timely manner. As we observed in Case Study #1, a bottom-up approach is an alternative view when considering conservation and restoration techniques. Utilizing community-based conservation, rather than fully leaving such initiatives to the hands of government agencies, we can allow local communities to step in and influence the use of these biomes. In the case of Appalachia, local communities most affected by deforestation as a result of surface mining could be given more of a say and a foot in the door when it comes to the restoration efforts implemented by surface mining companies.

As restoration efforts proceed, it is important to emphasize inclusivity. This can be seen in different ways, such as when we discuss taking a bottom-up approach that involves local communities. Policymakers and higher-up organizations are important and necessary when it comes to larger decisions, but empowering smaller groups allows us to improve education and our overall understanding of restoration and ensures no one is left out. Traditional Ecological Knowledge is also critical to inclusivity because of its holistic approach, as it incorporates differing worldviews and sustainable approaches. Incorporating TEK in policymaking and restoration efforts helps involve indigenous people who are frequently left out of the decision-making process.

In addition to this perspective change, the use of tools such as the Reforestation Hub could also contribute to cost-effective restoration techniques and allow organizations, local communities, and agencies responsible for restoration to accurately monitor and evaluate which areas need to be focused on and which can be left to natural regeneration. Mapping can be used in conjunction with this tool, which can assist in determining where the focus needs to be placed and how effective different methods are. Before any hands-on restoration is implemented, studying the land in its past and present state is important to determine how our restoration efforts will succeed in the future. Mapping and monitoring also help prevent a lack of attention in areas that need it most or too much labor and attention to areas that could benefit simply from natural restoration. Setting proper targets and monitoring progress can encourage cost-effective and efficient restoration.

Utilizing standards based on services and agencies such as the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, as well as the State Forest Service in New Zealand, could help provide a guide for this level of monitoring and intervention and could be regulated by policymakers and government powers. Implementing specific measures based on location and conditions that quantify what “rich biodiversity” should look like, as well as the other standards that are fostered by the US Fish and Wildlife Service, could assist in managing forests and restoring land where deforestation has occurred. Methods such as evaluating and monitoring exactly which areas should be deforested, if any, based on the availability of native tree species as encouraged by the State Forest Service could also be utilized in this way. As previously mentioned, advancements in monitoring and restoration could lead to increased costs and labor. To combat this, organizations could encourage volunteers and academic scholars to partake in this monitoring and restoration. In the case of Appalachia, these standards could be applied to require surface mining and logging companies to evaluate their regions of the land for effective restoration and prevent further unsustainable practices.

By observing varying techniques inspired by these case studies, we can begin to evaluate and propose methods to be applied to the Appalachian region and expand upon Project Drawdown’s mindset. While assessing which methods will benefit these restoration initiatives' future outcomes is difficult, implementing and experimenting with different techniques could be beneficial, as we have seen an array of approaches and success rates worldwide. Passive restoration tools, such as those seen in the case of New Zealand, could be utilized as a step above Project Drawdown’s natural restoration approach. In this case, non-native tree species could be dispersed and planted in and around indigenous temperate forests. This could guide the forest in regrowth but does not necessarily require consistent intervention and labor. Once the trees are planted, work can be left up to nature to help promote growth. If funds and labor are available, and specific regions need more attention than others, as analyzed by monitoring processes, then we could begin to implement more hands-on approaches and human intervention through silviculture techniques. The level of labor can be developed and dependent upon the current state of our forests and according to future needs and advances.

Conclusion

The findings from this article hold significant value to the future of forest restoration, as we address all scales of restoration rather than the top-down, overgeneralized approach that frequently neglects smaller-scale needs for underresourced communities and environmental variability due to climate change. Temperate forest restoration is an environmental, social, and economic discipline, and this paper addresses how we can avoid the possible mistake of only attending to one of those. We attempt to achieve this through a framework that focuses on environmental needs, the cost-effectiveness of actions toward restoration, and taking a bottom-up approach that works to empower individuals and communities. Future research on this subject should look at the functionality and resilience of ecosystems as a standard for what defines a healthy ecosystem and successful restoration, because recreating what a forest once was may not be what the ecosystem needs. Moving forward, researchers should not be hesitant to challenge existing paradigms and should consider the ever-changing needs of the environment and people of different socioeconomic statuses. Temperate forest restoration is a major part of fighting climate change, and we must maintain high levels of academic, financial, and emotional investment to repair the destructive actions of the past and create a better future.

References

Adams, Mary Beth, Charlene Kelly, John Kabrick, and Jamie Schuler. “Temperate Forests and Soils.” Global Change and Forest Soils, 2019, 83–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-444-63998-1.00006-9.

American Forests, and The Nature Conservancy. “Reforestation Hub.” Reforestationhub.org, March 21, 2023. https://www.reforestationhub.org/.

Apfelbaum, Steven, Alan Haney, and Alvaro F Ugalde. “Bottom-up versus Top-down Land Conservation - Non Profit News: Nonprofit Quarterly.” Non Profit News | Nonprofit Quarterly, February 19, 2013. https://nonprofitquarterly.org/bottom-up-versus-top-down-land-conservation/.

“Appalachian Regional Reforestation Initiative.” Appalachian Regional Reforestation Initiative | Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://www.osmre.gov/programs/arri.

Barton, Andrew M., William S. Keeton, and Thomas A. Spies. Ecology and recovery of eastern old-growth forests. Springer Link. Washington ; Covelo ; London: Island Press, 2018. https://link.springer.com/book/10.5822/978-1-61091-891-6.

Benson, Craig. “More than One-Third of U.S. Counties Had Declining Poverty Rates in 2018-2022.” Census.gov, December 21, 2023. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2023/12/poverty-rates-by-county.html.

“Conserving the Appalachians.” The Nature Conservancy. Accessed April 26, 2024. https://www.nature.org/en-us/about-us/where-we-work/priority-landscapes/appalachians/.

Davis, Victor M., Patrick Angel, Jim Burger, Don Graves, and Carl Zipper. “Appalachian Regional Reforestation Initiative and the Forestry Reclamation Approach.” Journal American Society of Mining and Reclamation 2007, no. 1 (June 30, 2007): 200–205. https://doi.org/10.21000/jasmr07010200.

Digital NC. “Boone 1903-1904.” DigitalNC, January 1, 1970. https://lib.digitalnc.org/record/5940?ln=en&v=uv#?xywh=-1844%2C-275%2C8662%2C4485.

Dumroese, R. Kasten, Mary I. Williams, John A. Stanturf, and J. Bradley Clair. “Considerations for Restoring Temperate Forests of Tomorrow: Forest Restoration, Assisted Migration, and Bioengineering.” New Forests 46, no. 5–6 (August 2, 2015): 947–64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11056-015-9504-6.

Forbes, Adam S., David A. Norton, and Fiona E. Carswell. “Opportunities and Limitations of Exotic Pinus Radiata as a Facilitative Nurse for New Zealand Indigenous Forest Restoration.” New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science 49 (July 5, 2019). https://doi.org/10.33494/nzjfs492019x45x.

Galicia, Leopoldo, and Alba Esmeralda Zarco-Arista. “Multiple Ecosystem Services, Possible Trade-Offs and Synergies in a Temperate Forest Ecosystem in Mexico: A Review.” International Journal of Biodiversity Science, Ecosystem Services & Management 10, no. 4 (October 2, 2014): 275–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/21513732.2014.973907.

Halme, Panu, Katherine A Allen, Ainars Aunins, Richard H.W. Bradshaw, Guntis Brumelis, Vojtech Cada, Jennifer L Clear et al. “Challenges of Ecological Restoration: Lessons from Forests in Northern Europe.” Biological Conservation, September 18, 2013. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0006320713003030.

Kiprop, Victor. “Continents by Population Density.” WorldAtlas, April 17, 2019. https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/continents-by-population-density.html.

Lara, Antonio, Julia Jones, Christian Little, and Nicolas Vergara. “Streamflow Response to Native Forest Restoration in Former Eucalyptus Plantations in South Central Chile - Authorea.” Research and Observatory Catchments: The Legacy and the Future, May 2021. https://www.authorea.com/doi/full/10.22541/au.160157479.99029731.

Maldvakar, Urmila, Mamta Mehra, Eric Toensmeier, and Chad Frischmann. “Temperate Forest Restoration.” Project Drawdown, 2AD. https://drawdown.org/solutions/temperate-forest-restoration.

McGlone, Matt S., Peter J. Bellingham, and Sarah J. Richardson. “Science, Policy, and Sustainable Indigenous Forestry in New Zealand.” New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science 52 (March 24, 2022). https://doi.org/10.33494/nzjfs522022x182x.

Oxford Reference. “Simpson’s Diversity Index.” Oxford Reference. Accessed April 28, 2024. https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803100507460.

Perks, Rob. “Mountaintop Removal: Farewell to Forests.” Be a Force for the Future, April 16, 2010. https://www.nrdc.org/bio/rob-perks/mountaintop-removal-farewell-forests-0.

PhycoTerra. “Soil Health Indicators: How to Improve Your Soil Health.” PhycoTerra®, October 4, 2023. https://phycoterra.com/blog/soil-health-indicators/.

Robinson, Cal. “Four Elements of a Healthy Forest: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.” FWS.gov, October 11, 2022. https://www.fws.gov/story/2022-10/four-elements-healthy-forest.

Souther, Sara, Sarah Colombo, and Nanebah N. Lyndon. “Integrating Traditional Ecological Knowledge into US Public Land Management: Knowledge Gaps and Research Priorities.” Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 11 (March 9, 2023). https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2023.988126.

Unknown Author. “How We Work.” The Nature Conservancy. Accessed April 28, 2024. https://www.nature.org/en-us/about-us/who-we-are/how-we-work/.

Unknown Author. “Our Mission.” Blue Ridge Conservancy, 2024. https://blueridgeconservancy.org/.

Wright, A.J., L. Mommer, K. Barry, and J. van Ruijven. “Stress Gradients and Biodiversity: Monoculture Vulnerability Drives Stronger Biodiversity Effects during Drought Years - Wright - - Ecology - Wiley Online Library.” Ecology Society of America, September 9, 2020. https://esajournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ecy.3193.

Zipper, Carl E., James A. Burger, Jeffrey G. Skousen, Patrick N. Angel, Christopher D. Barton, Victor Davis, and Jennifer A. Franklin. “Restoring Forests and Associated Ecosystem Services on Appalachian Coal Surface Mines.” Environmental Management 47, no. 5 (April 11, 2011): 751–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-011-9670-z.